- Welcome

- Family History

- Letters & Diaries

- Folder: 1940 - 1999

- Name: Charles Wythe Gleaves Rich, West Point Class of 1935

Name: Charles Wythe Gleaves Rich, West Point Class of 1935

Name: Charles Wythe Gleaves Rich, West Point Class of 1935

- » Date: 1988-10

- » Subject: Name: Charles Wythe Gleaves Rich, West Point Class of 1935

- » Written By: Joe Gray

- » Addressed To: Islander Magazine

Page 1

Islander Magazine/October 1988

Stars Fell On Hilton Head

This is the seventh in Islander’s series of articles on retired generals and admirals who have made Hilton Head Island their home.

By Joe Gray

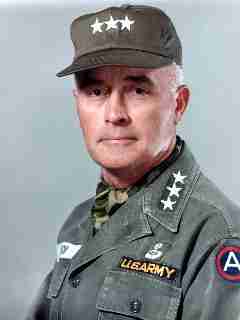

Name: Charles Wythe Gleaves Rich, West Point Class of 1935

Address: 95 South Port Royal Drive, Port Royal Plantation

Rank: Lieutenant General, U.S. Army, retired

When Hilton Head Island’s highest-ranking retired airborne commander was going through parachute school, you might say he got off on the right foot. Or feet.

On a spring day in 1943, then Lieutenant Colonel Chares W. G. Rich was to be the first man in his class at Fort Benning, Georgia, to jump from a 250-foot-tall tower in a demonstration for a group of VIPs.

As Charlie Rich recalls it: “There wasn’t a breath of ground wind when they hoisted me to the top of the tower. When I was about halfway down, however, a strong wind came up and I had to pull hard on my risers in an attempt to avoid the crowd below.

“The wind proved to be too strong, though, and I landed practically in the lap of my commander in chief, President Franklin Roosevelt!”

This fledgling parachutist was to go on to become one of the Army’s top airborne leaders both in war and in peace. Among his key posts was as Commanding General (1961-1963) of the famed 101st Airborne Division, that stubborn outfit that withstood the German assault on Bastogne in World War II’s Battle of the Bulge.

Charles Rich was born in Bandy, Virginia, on December 22, 1910. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1929 and was assigned to Langley Field, Virginia, until June, 1931.

During this time he attended the United States Military Academy Preparatory School at Fort Monroe, Virginia. He was graduated from West Point in 1935 with a Bachelor of Science degree and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant of Infantry.

While at West Point, Rich lettered in track, participating in the hurdles and broad jump. He was good enough to have won the 440-yard hurdles at the Metropolitan AAU meet and placed third in the National AAU meet in the same event.

Charlie Rich remembers a story about two errant cadets who picked the wrong day to go “sightseeing.”

“The Hudson River is the eastern boundary of West Point – east of the Hudson was ‘OFF LIMITS.’ One cold, wintry afternoon when the Hudson was frozen over, two ‘pioneering’ cadets from the class of ’36 decided to ‘go for it’ and crossed the river on the ice to see what interesting items might be on the other side – such as pretty young ladies.

“At the end of the day, when the sun was setting, these two gallant explorers returned to the east bank of the Hudson where they found to their horror that the Hudson was now flowing freely where they had crossed earlier – the ice cutter had passed during their absence!

“Needless to day, the Corps of Cadets gave those two gallants a roar of welcome when they came into the Mess Hall one hour late that evening – after an unprogrammed walk of six miles!”

The next 35 years saw Rich undertake many assignments, both in the United States and overseas, and rise in rank from “Shavetail” to three-star General.

During the early part of World War II he served in the 19th Infantry Regiment in Hawaii. Among his assignments was Commanding Officer of the 2nd Battalion. From March, 1943 until October, 1944, he was posted to the Infantry School in Fort Benning, Georgia, where he attended parachute school.

Eventually he became the school’s Executive Officer with the rank of Colonel. Later he served in Europe with assignments as Airborne Adviser, G-3 Section, XXI Corps; G-1 and Chief of Staff Oise Base Section; Chief of Staff, Western Base Section, and Assistant to the Deputy Chief of Staff, USFET (U.S. Forces, European Theater).

During the Allied advance toward the Rhine, and after the capture of the bridge at Remagen, Colonel Rich became involved in an attempt to seize another bridge – this one at Speyer, Germany.

He tells it this way: “About March 27, 1945, the Seventh Army was in the process of seizing the western bank of the Rhine between Mainz and Karisruhe. About 8 p.m. the Army called the XXI Corps and informed them that the bridge at Speyer, some 10 miles south of Ludwigshafen, was still standing. ‘Can you capture it before it is dropped in the river?’ (XXI Corps was asked).

“My Corps Commander, General Milburn, dispatched me to see if the 12th Armored Division or the 71st Infantry Division could be diverted to this task.

“Enroute, I dropped off my jeep and borrowed a combat car with a Reconnaissance Captain and took to the east across the plain at Pirmasens. Almost immediately we heard a loud explosion under our vehicle – fortunately it was an anti-personnel mine and the command car was not unduly damaged.

“Shortly thereafter, as we were passing through a German village, we saw white flags hanging out of the windows of the houses along the road. ‘They have surrendered,’ the Captain said. As we proceeded, the number of flags became fewer and fewer, and, finally, there were none – we were now in, and going through, the German lines. A little later the road we were traveling on ended, and after a short pow-wow we turned north.

“The Germans apparently had gone south, or were sleeping, or both. After going about one or two miles to the north, we ran out of the German lines and suddenly were stopped by an American sentry who said, ‘Halt, who’s da?’

“’Friend,’ I answered and he advanced toward me. Quickly I said, ‘Soldier, take me to your officer.’ He said, ‘Follow me.’ (Stonewall Jackson’s last ride flashed through my mind, but I had been luckier – I didn’t know the password, either).

“In a few moments (it was 3 a.m.) I was in the presence of General Red Allen of the 12th Armored Division. He said that his division last evening pulled back from where we had come. I then went out in the night, found the 71st Division, watched them dispatch a regiment which arrived in trucks 500 yards short of Speyer, and daylight had come. The Germans then blew the bridge. (We were) a mite too late!” Shortly after this episode, Rich was awarded the Silver Star.

Following his return to the States, Rich was assigned to the Armed Forces College as student officer, then instructor, and later as Secretary of the College. In July, 1950. he went to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where he served as Regimental Executive Officer and Division Chief of Staff. He attended the Army War College in 1952-1953.

His next overseas tour was in Korea from September, 1953 to September, 1954. He was Commanding Officer, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division, and Deputy Chief of Staff, Headquarters, IX Corps.

One of Charlie Rich’s fondest recollections of Korea came when a member of his 15th Infantry Regiment, Sergeant 1st Class Ola Mize, received the Congressional Medal of Honor and promotion to Master Sergeant following many heroic actions as a squad leader. “These two awards in one day were well deserved,” Rich says.

Mize later attended Officer Candidate School in Fort Benning, climbed steadily in rank and retired several years ago as a full Colonel.

After a Washington assignment, Rich became Commandant of Cadets at West Point and served two stints with the 101s Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He became Commandant of The Infantry School at Benning in February, 1963.

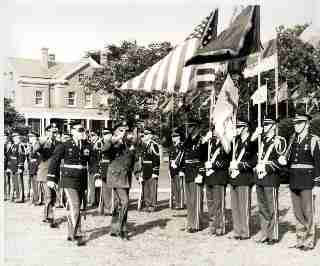

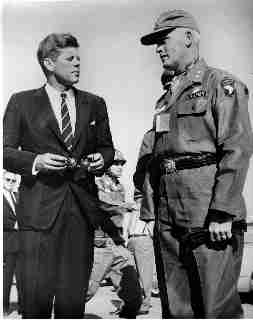

During his tenure as Commandant of Cadets, several things stand out in Rich’s memory. One was leading the Corps of Cadets down Pennsylvania Avenue on January 20, 1961, during the inaugural parade for President John F. Kennedy. “It was colder than the Arctic,” Rich recalls, “but it was a great honor.”

A second, and traumatic, episode involved the West Point Honor Code. A cadet had taken a quarter intended for somebody else from his roommate’s bunk and spent it on some candy. The Cadet Honor Board found him guilty, Rich upheld the verdict and the young man was expelled.

The cadet’s parents came to General Rich’s office in an effort to get their son reinstated. “The mother did all the talking,” Rich says. “She asked me if I had a son. I said no but that I had two daughters in college, one at William and Mary and the other at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.”

“Do those schools have codes?” she asked.

“I replied yes, but that at West Point we were training officers to lead men in combat. I cited as an example a young Infantry platoon leader ordered to take his men on a night patrol to determine enemy strength in front of their sector.

“intelligence information must be gathered even if some members of the patrol become casualties. That information has to go back to the General commanding the units in battle.

“If this one platoon leader turns tail after someone is shot, this lack of intelligence information could affect the entire outcome of the battle. Your mission must be accomplished.” (Rich interjects at this point that the lesson to be learned from this is “tell the truth and persevere.”)

“The cadet’s mother wept, but his father said, ‘Your example convinces me 100 percent.’”

While he was Commanding General of the 101st, Major General Rich’s paratroopers were summoned to assist National Guard units and police when James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi in Oxford.

Protesters vowed that Meredith would not be enrolled and several ugly incidents occurred. On the night of September 30, 1952, the protesters (“rednecks,” Rich calls them) and Guard troops had a tussle; weapons and tear gas were used.

The 101st sped to Oxford by truck, arriving in a rainstorm which added to the confusion. “We set up road security, city security, and University security,” Rich recalls. “Five more divisions arrived during the day.

“By the next day, the situation was under control, the other divisions returned to their stations, and Meredith moved from his dormitory to classes with only occasional incidents.” Local police took care of Meredith’s security after the 101st returned to Campbell.

The 101st also was called upon in the late 1950s to rescue Vice President and Mrs. Nixon in Caracas, Venezuela, after an unruly mob surrounded the building in which they were staying and they feared for their lives. The Nixons were on a goodwill mission at the time.

Rich and his troopers formed a Battle Group Task Force and set off by air to the rescue. While the Task Force was refueling in Puerto Rico, however, word was received that the Venezuelan mob was under control and the Nixons were able to leave in their aircraft for a stop in Rome.

“The disappointed Task Force also returned home,” Rich says, “but proud of their performance as the first Alert Task Force to go on such a mission.”

On August 1, 1964, Rich received his third star as Lieutenant General and assumed command of the Third United States Army at Fort McPherson, Georgia. (This was the same command that Hilton Head resident Bert Connor held later on. See Islander’s May, 1988 issue.)

Rich’s final assignment was as Deputy Commanding General, Continental Army Command at Fort Monroe, Virginia, in the state of his birth.

In addition to his Silver Star, Rich was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster, the Bronze Star and the Army Commendation Ribbon. Among his foreign decorations are the French Legion of Honor, French Croix de Guerre with two Palms, the Polish Order of Polonia Restituta IV Class, the Belgian Croix Militaire Pre Class, and the Korean Order of National Security Merit, II Class.

Rich retired from the Army on August 1, 1970, then moved to Hilton Head where he lives with his second wife, Eleanor, in their beautiful home on South Port Royal Drive. From their second-floor, glassed-in porch, the Riches have a view of the Atlantic through the live oaks at the back of their property.

Eleanor and Charlie have been long-term volunteers at the Hilton Head Hospital and both enjoy gardening. (“She’s the boss,” Charlie laughs.) Her roses are a treat for the eye. Charlie, a former member of the Senior Men’s Golf Association, still plays although his handicap has risen over the years.

Rich and his first wife, Betty, had two children: Mrs. Joseph T. (Anne) Palastra, Jr., of Atlanta, and Mrs. Terry M. (Roselyn) Smith of Kona, Hawaii. The General has six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Charlie Rich today still has a distinct military bearing – all 6’ 1½” of him. His hair is whiter now that he is nearing 78 and his legs are affected by a diabetic condition.

But, as Harold H. Martin wrote in the September 9, 1950, Saturday Evening Post in an article “The Colonel Saved The Day” about Colonel John Michaelis in Korea: “There is something about a paratrooper that never leaves him until he dies – an insouciance, a swagger, a cocky confidence.” Amen.

Page 4

With President John F. Kennedy at Fort Campbell, Kentucky